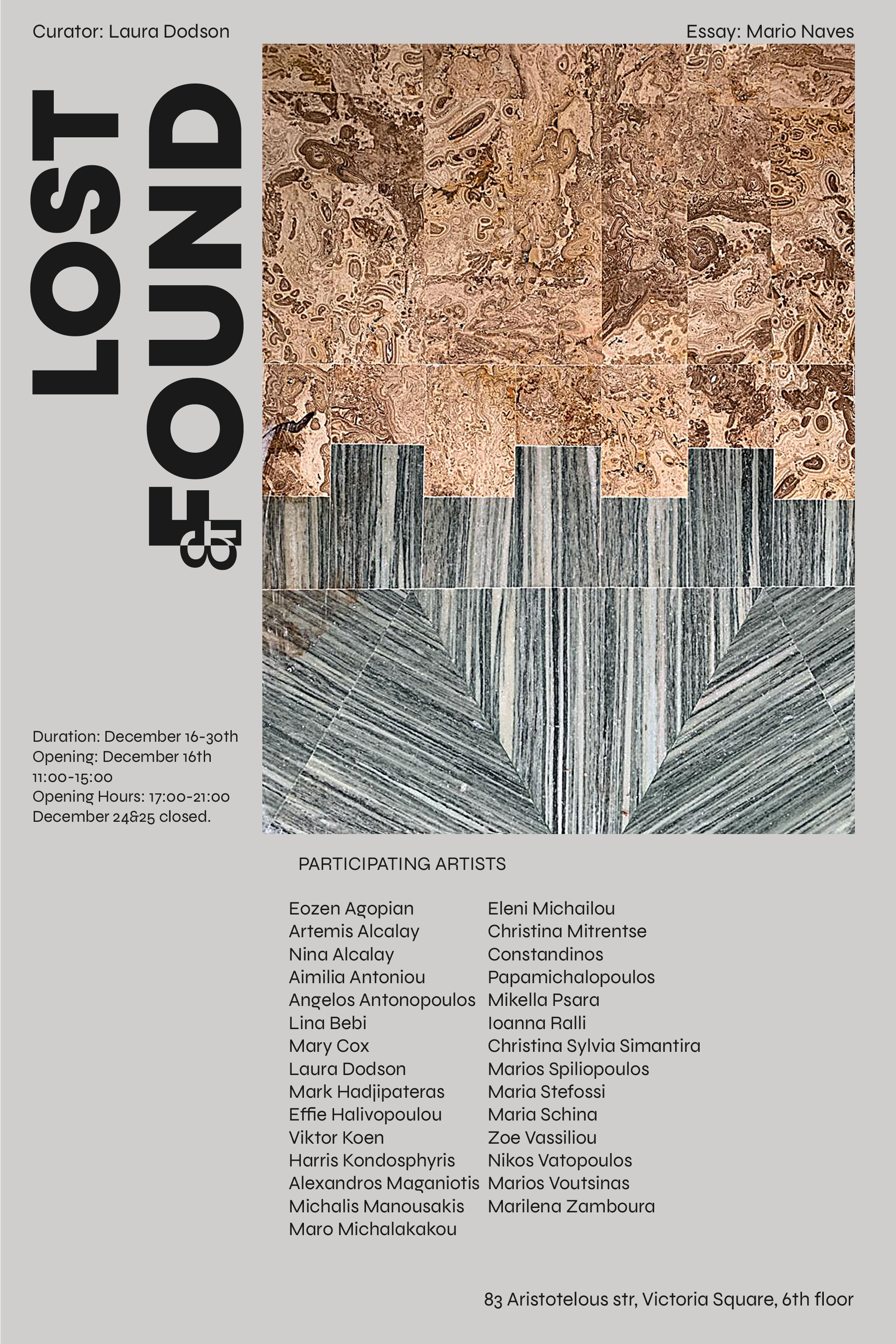

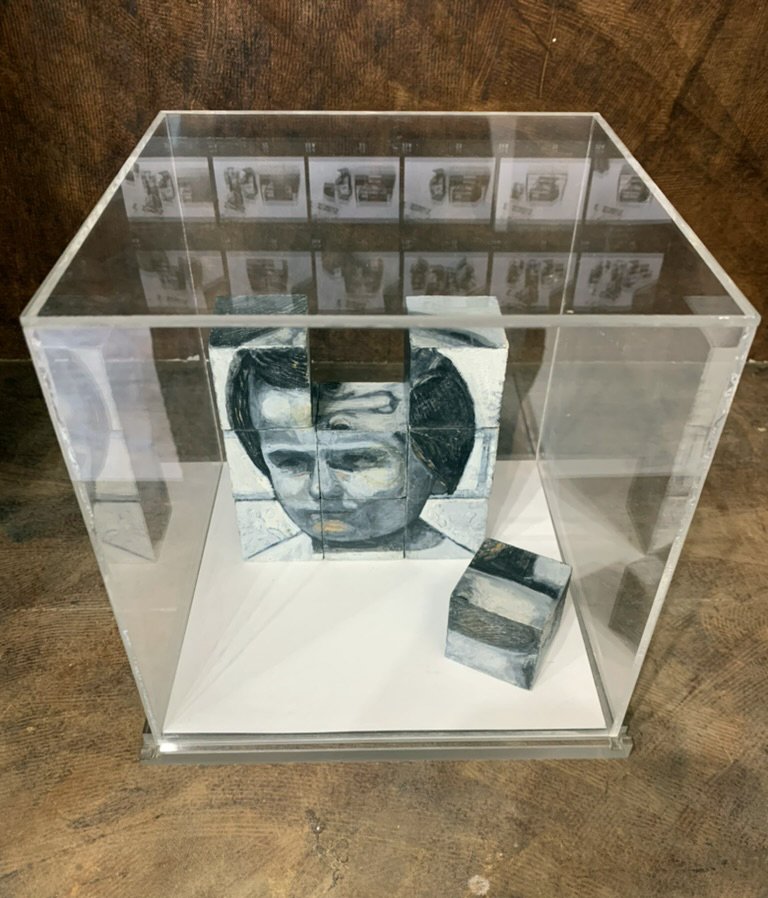

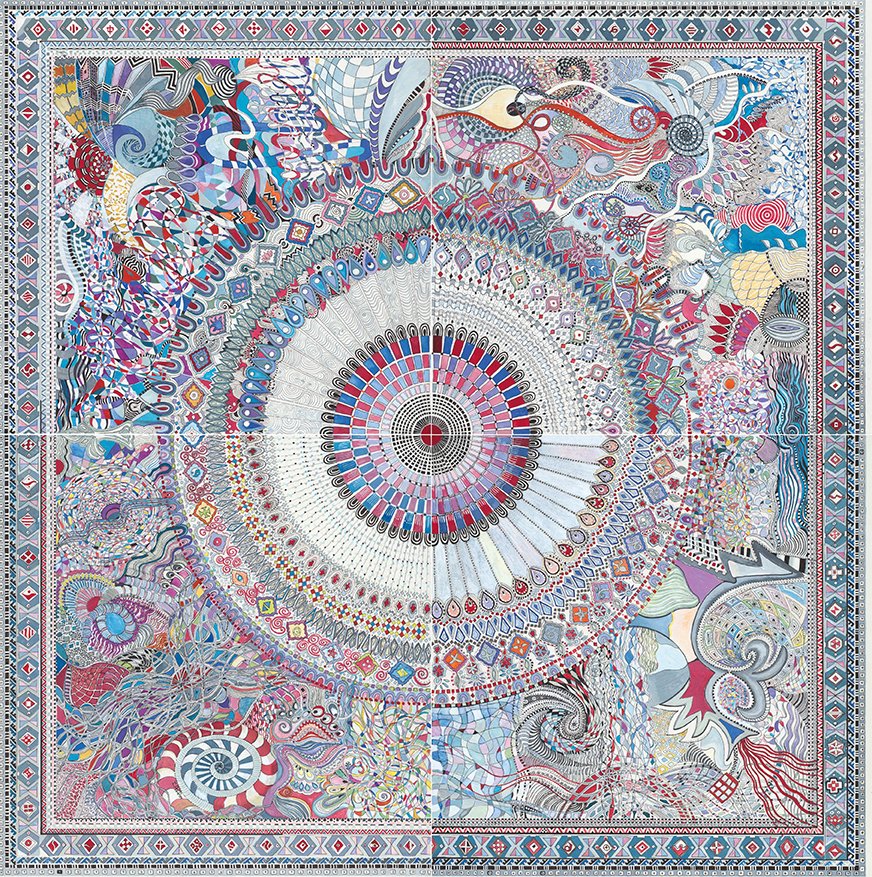

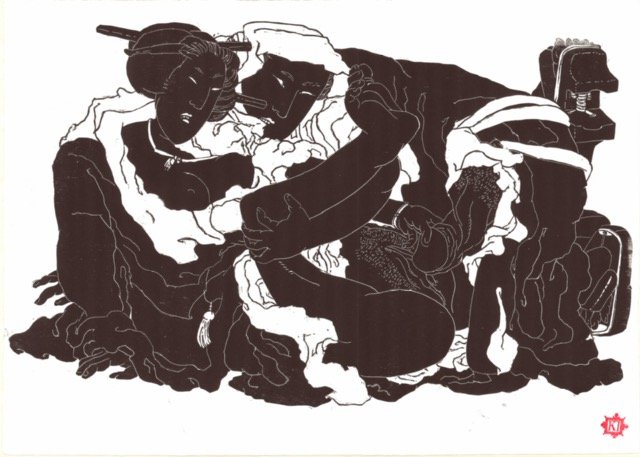

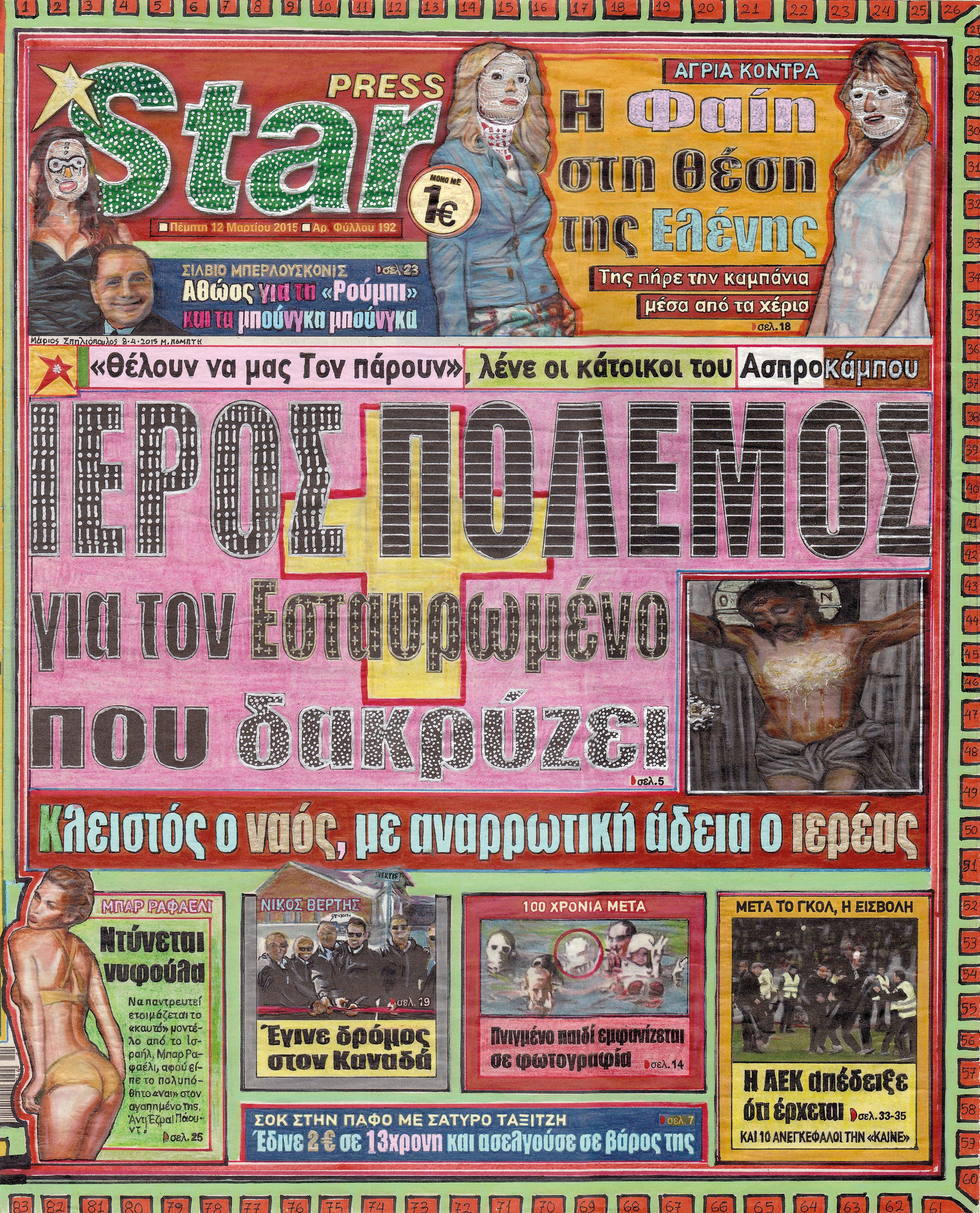

LOST AND FOUND EXHIBITION

Curator: Laura Dodson

DECEMBER 2023. ATHENS, GREECE

Inspired by the reclaiming of an Athenian apartment in the historic neighborhood of Victoria Square, the exhibition LOST and FOUND will delve into themes of memory, transformation, and repurposing within the framework of an architectural maze. In this unique setting, a space that is being renovated into a working studio, 28 artists of Greek descent will reflect on the evolving landscapes of time and place, on the rejuvenation of forgotten objects, and on recollections from their own historical narrative

AIPAD 2022 New York

The AIPAD Photography Show has arrived in New York to create its annual buzz. This art fair is a magnet for both seasoned and curious photography collectors, museum curators, art historians, critics, and lens-based artists, all vying for a coveted vintage print, or a purview of the ever-evolving advances of the medium.

The 49 exhibiting galleries of AIPAD are united around a pledge of excellence regarding the quality and integrity of the art they represent, as well as a code of ethics when it comes to selling or buying. Camaraderie, rather than competition, prevails among the dealers, who form a tight community with a shared history, a profound respect for the medium, and a mutual interest in educating people about fine art photography.

While AIPAD is not the marketing venue for the Instagram snap-shooter, it is refreshingly non-exclusive once its doors open to the public. True, gear geeks in camera vests trawling for the latest Nikon lens might scratch their heads upon entering, but everyone is welcome, and the excitement is palpable. During its weekend run, the show packs a crowd of followers and enthusiasts, sophisticated or green, whose interest in photography is heralded by a capital P for Passion.

The field of photography and its market is relatively contained, often threatened by extinction, yet constantly shape-shifting and persevering. Since its inception, the medium has survived a state of flux and many a blindside.

Remember when you went to an old-fashioned studio to get your picture taken? Remember when those professionals were replaced by amateurs with Kodak hand-held cameras? Remember the cellulose strips called negatives, and how color invaded their monochromatic stronghold? Remember when Kodak closed, when digital technology usurped chemicals and darkrooms, then when smartphones and the internet took over whatever remained?

Happily, the exhibitors at AIPAD have made it their life’s work to remember. History and change are embraced and integrated throughout the fair’s booths. Subject matter, reality driven or completely fabricated, presents itself in a cross fertilization of materials and methods. Abstraction, new media, and manipulated imagery share the floor with staunch and straight classicism.

Old schoolers pining for the unassuming charm of 20th century gelatin silver-prints can peruse vintage collections throughout the fair. Admirers of 19th century processes will unearth some treasures. And finally, followers of contemporary idols and trends will not be disappointed.

What is ultimately wonderful about AIPAD is that the offerings are as diverse as their audience. Visitors can navigate the maze of booths toward their respective niches. Along the way, they will be enticed and stirred by many surprises.

The 2022 Photography Show presented by AIPAD will be held at Center415 (415 Fifth Avenue between 37th and 38th streets) and will run 4 days from the 20th till the 22nd of May, with a VIP preview on the 19th. For further information and tickets: AIPAD.com

William Klein: YES

June 3rd - September 12th, 2022 at The International Center of Photography

William Klein, Gun 1, New York, 1956

Nina + Simone, Piazza di Spagna, Rome (Vogue), 1960

William Klein, “Bikini, Moskva (River), Moscow,” 1959

Kazuo Ohno, Yoshito Ohno, and Tatsumi Hijikata … Tokyo, 1961

PDFs appearing below were published between 1995 and 2015 in Greece’s monthly PHOTOGRAPHOS MAGAZINE. Articles are in Greek, and English translations are forthcoming.

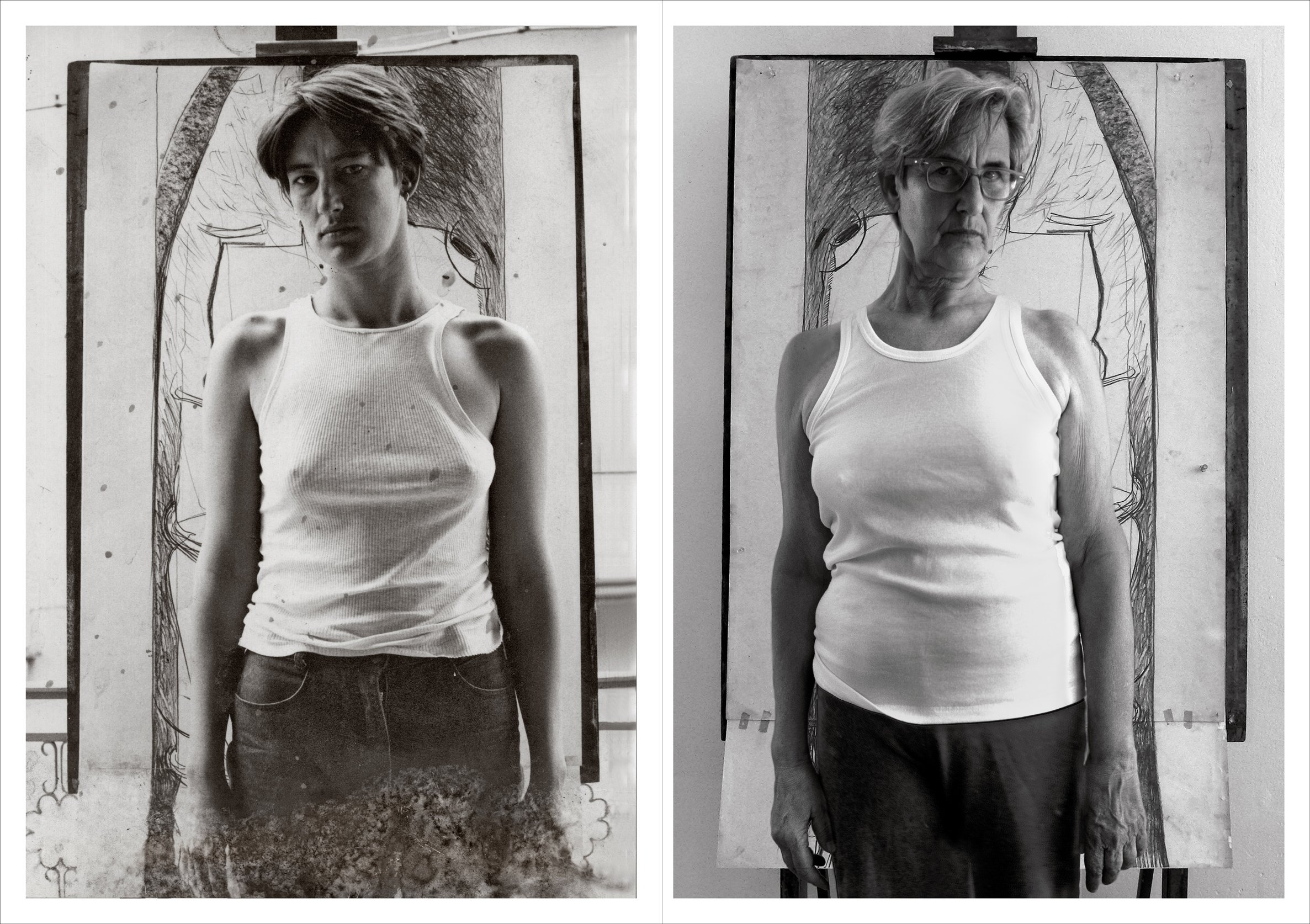

Sally Mann, Hephaestus, 2008

INTERVIEW

Below the artist discusses “Proud Flesh” (2009) published by Aperture and currently on exhibit in New York’s Gagosian Gallery.

1. You have photographed the cycles of nature and family, the transition of children into adulthood, the decaying bones of your dog, plots of land which are charged with ancestral memory… Could you elaborate on the common thread that binds your vision and your approach to shooting?

It has been my philosophy to make art out of the everyday and ordinary. Most of the pictures I take are of the things I love, the things that fascinate and compel me. My family and my land give me the inspiration for my work, but that doesn’t mean they are easy to look at or to take. Like Flaubert, two things are sacred to me in my process: impiety and perfection, the former often hereditary, the latter always hard-won.

2. You have stated that you “pray for the angel of uncertainty to visit your photographic plate”. This tends to refute the methodology of masters such as Adams who believed in pre-visualization and absolute control. Would you say you are balancing control with accident, and to what purpose?

Beyond the felicitous, unifying accidents that occasionally grace the work, making art requires tenacity, a temperament born of an ungodly cross between a hummingbird and a bulldozer, and, most of all, practice. Practice looking.

3. Your husband has been an ongoing subject over the years… could you discuss your photographic relationship?

I have looked hard at my husband since the first long strides he took into the room where I was languishing on a ratty chenille couch in some student apartment. My eyes fastened on him with bright interest, squinting to better get the measure of this tall man. Within six months we were married. That was forty years ago, and almost the first thing I did was photograph him.

Recently, Larry and I began this work of exploring what it means to grow older, to let the sunshine fall voluptuously on a still-beautiful form, and to spend quiet afternoons together again. No phone, no kids, two fingers of bourbon, the smell of the ether, the two of us still in love, still at work.

4. Is gender an important issue in your work?

I am a woman who looks. Within traditional narratives, women who look, especially women who look unflinchingly at men, have been punished. Take poor Psyche, punished for all time for daring to lift the lantern to finally see her lover.

I can think of numberless males, from Bonnard to Callahan, who have photographed their lovers and spouses but I am having trouble finding parallel examples among my sister photographers. The act of looking appraisingly at a man, making eye contact on the street, asking to photograph him, studying his body, has always been a brazen venture for a woman, though, for a man, these acts are commonplace, even expected.

5. The history of naked male representation tends to support an Apollonian or action ideal. Some of your titles Discobolos/David reference classic beauty and potent energy, whereas in effect your protagonist submits to the passive role of the sitter. Are you deliberately attempting to soften him, to accent his vulnerability and physical imperfections?

It is a testament to Larry’s tremendous dignity and strength that he allowed me to take the pictures that I did. The gods might reasonably have slapped this particular lantern out of my raised hand, for before me lay a man as naked and vulnerable as any wretch strung across the mythical, vulture-topped rock.

6. Would you expect this series to be viewed as both tender and harsh?

I look, all the time, at the people and places I care about, and I look with both ardor and frank, aesthetic, cold appraisal. And I look with the passions of both eye and heart, but in that ardent heart, there must also be a splinter of ice.

At our ages, we are past the prime of life, given to sinew and sag, and Larry bears, with his trademark god-like nobility, the further affliction of a late-onset muscular dystrophy. That he was so willing is both heartbreaking and terrifying at once,

7. Artists you mentioned and more, such as Stieglitz, Weston, and Gowin who made nudes of their female partners were often accused of exposing, objectifying and stereotyping them. Do you foresee your new series as being susceptible to such criticism?

Exploitation lies at the root of every interaction between photographer and subject, even forty years into it. Larry and I both understand how ethically complex and potent the act of picture-taking is, how freighted with issues of honesty, responsibility, power, and complicity, and how so many good images come at the expense of the sitter, in one way or another. These new images, we both knew, would come at his.

William Klein, 94, left his mark on the history of photography as a mid-century street shooter. His prominent images of the fifties were important satellites to what became a popular and influential genre.

The current retrospective at the International Center of Photography aims to shift that narrow purview of Klein’s accomplishments, in favor of an expansive survey of his multifaceted career. The title of the exhibition William Klein: YES; Photographs, Paintings, Films, 1948-2013 says it all. Curator David Campany emphasizes the artist’s energetic approach by scanning six decades, several continents and a bevy of disparate yet integrated takes on creativity.

Born in New York, William Klein moved to Paris in 1948 on a GI bill in the hopes of becoming a painter. Apparently, Fernand Léger, whom he was studying with, recommended he branch out into the fields of the Graphic Arts and Photography. Fast forward through a few art exhibits, experiments with abstraction and cameraless images, and we find Klein multitasking for ritzy Vogue Magazine, while fanatically taking his camera to record New York’s non -glamorous side of the tracks. He followed up with incredible photographic documents of Tokyo, Rome, Paris, and Russia.

And then, he quit photography, excited by the possibilities of seemingly every related medium. He made noisy caustic films, experimental, documentary, and full feature fiction. He published cheeky posters and designed his own books with iconoclastic style. He blew up his contact sheets and painted on them in bold primary colors, restlessly intensifying the 35mm negative’s relationship to cinematic sequences.

Curators are aware that today’s audiences seek what has commonly become known as an immersive experience, art that seduces with color and sound and movement. Let’s face it, a black and white street photographer, a –gasp— silent generation, pre-boomer with an analog camera, stands little chance of drawing attention.

But thanks to William Klein’s maverick nature, the show does not disappoint. It all crackles and connects at ICP. Here is one dog the curator did not need to teach new tricks to. Campany lets him loose in the playground. A montage aesthetic, check. Interchangeable media, check. Loud big noisy tactics, check. Some glamour and glitz, check. Plenty of grimy grit, check. A global perspective, check. An underdog activist’s passion for humanity, diversity and difference, check, check, and check.

Nevertheless, it is on ICP’s second floor where we need to thank Fernand Léger for steering Klein to what was then considered the “lesser art form” of Photography. Editing and branding him within the street niche of the 50s or the fashion tide of the 60s may seem limiting by today’s standards, but back then it was where the cool kids played. Think of influences as heady as the Beat poets, Jazz musicians, and Abstract Expressionists, all applied to the rhythms of the metropolis. Think Robert Frank’s The Americans and how it became an opus to the dispossessed.

What blossomed from this aesthetic after 1960 (when Klein had alas dropped the camera) was not just Frank, but a massive change in photographic perception, relating greatly to sociopolitical unrest. Vietnam, racial riots, assassinations, the hippy movement, all led to some of the history’s best photographic series: Diane Arbus’ unflattering portraits, Larry Clark’s junkies in Tulsa, Gary Winogrand’s sardonic grasp of everything comic and tragic about city life.

It seems Klein instinctively foresaw this shift. Despite his years in Europe, from where the big names of street photography (Atget, André Kertész, Robert Doisneau and of course Henri Cartier Bresson) performed lyrical arabesques with their cameras, Klein was a true American. He eschewed beaux arts elegance for confrontation, noise, and causticity. Rhythms, repetitions, touches of light, balancing shadows, and slices of time -- all that graceful choreography that made Bresson a master, were secondary to Klein’s hunger for involvement.

In his approach to art, William Klein was more like a bull in a china closet. He put his body rather than his eye into his endeavors, shooting from within the fray rather than composing carefully from without. He got close, albeit with a wide-angle lens, which allowed him to catch the action as well as its clumsy periphery. This is a metaphor for the philosophy behind William Klein’s entire body of work, and it is fittingly on view at ICP. Things may seem loose around the edges, but they are gutsy, real, and in the moment.

Sally Mann: Proud Flesh

Gagosian Gallery 2009

Sally Mann’s subject matter embraces the quotidian, what she refers to as “art right under my nose”: her family, her homeland, her history… but her eye settles on these with extraordinary intent - critical, surreal, romantic – and plunges them into the disquieting narratives which have captivated her audiences for over four decades.

Her art is compelled by nature, evanescent beauty, shifting time, love, and the grand themes of adventure, mortality and eroticism that accompany these.

While consistently atmospheric and affecting on a visual level, the imagery gains additional emotional force from the photographer projecting herself on the experience. Case in point, her newest work “Proud Flesh”, an intimate, contemplative study on her husband Larry. In an unusual reversal of gender roles, it reveals artist and muse laboring side by side in a dialogue that exposes both. Sharing her thoughts on this new collection, she reflects:

“Larry and I began the work of exploring what it means to grow older, to let the sunshine fall voluptuously on a still-beautiful form, and to spend quiet afternoons together again. No phone, no kids, two fingers of bourbon, the smell of the ether, the two of us still in love, still at work.”

“No kids”… more remarkable a feat for this woman than others. Though already a seasoned artist, she came to sudden fame in 1992 with an impressive and provocative group of images depicting these children, their rituals, games, accidents, and calamities. Often posing naked as a factor of their natural surroundings, they nevertheless possessed an unnerving sensuality, product of their inherent grace and the photographer’s lush handling of her materials. Published by Aperture, the series, titled “Immediate Family”, rapidly became a bestseller, launching the photographer into international acclaim just as it flooded her in a wave of controversy, which included accusations of child pornography and neglect.

Over time Mann allowed the rural backdrops that had set the stage for her now grown protagonists to overtake the work. She began to focus on the evocative stretches of land that encircled her home.

Again, these images were emotionally charged, here by the burden of the South’s past, and by Mann’s proximity to it. She photographed battlegrounds, sites steeped in strife and the toil of slaves, grounds stained by lynchings, murder, blood.

Many of her landscapes appear womblike, humid and tentacled. Others ghostly, bleached and brittle, still others loom like ominous, charcoal expanses flecked by dust and blemishes.

As an offshoot of these, in the year 2000 she began to examine death more closely, concentrating on flesh as it decays, disintegrates into the earth, shifts and mutates with the passage of time. In the most disturbing chapter of this series, she gained access to a forensic facility (or “body farm”) and recorded decomposing cadavers with a scientist’s calculated attention, yet her customary expressive pen.

Nowhere is her obsession with altering states of matter better embodied and enhanced than on the faces of her textured plates. She controls the unexpected whims of her technique as abstract expressionists once engaged accidents of dripping paint. Her processes defy the digital revolution and refer us back to the 19th century, just as her working methods set her apart from her contemporaries.

She trudges through the fields of the American South lugging an 8X10 view camera the way soldiers bore their gear over the same terrain during the civil war. She equips her van with a mobile darkroom where she coats collodion over glass negatives. Her lenses, acquired in antique shops specifically for their distorting leaks warps and cracks, infuse her images with an idiosyncratic aura. An ancient enlarger and unpredictable kitchen chemistry complete her remarkable prints whose surfaces seem to breathe and bleed into her subject matter.

Thus, her current portfolio on Larry, examines his naked body as it succumbs to age and ill health, but mostly to her inquisitive gaze and molding hands, which cast him like a sculpture and envelop him in the moist veils of her emulsions. The pictures feel ancient… while matter and light accumulate, so do the objective manifestations of time. Acting as memory it appears, as a caress or a scar, leaving its inevitable touch on these intimate proceedings. ____________________________________________________

Sally Mann, Was Ever Love, 2009

Sally Mann, Ponder Heart, 2009

Sally Mann, Memory’s Truth, 2008

One of America’s most renowned photographers, SALLY MANN lives and works in Lexington, Virginia, where she was born in 1951. Mann has received numerous awards and her work is held by major institutions internationally. Her many books include “What Remains” (2003), “Deep South” (2005), and the Aperture titles “At Twelve” (1988) and “Immediate Family” (1992). A feature film about her work, “What Remains”, debuted to critical acclaim in 2005. Mann is represented by Gagosian Gallery, New York.

Lucas Samaras

Metropolitan Museum of Art 2014

ROBERT FRANK

Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009